For over 30 years Texas-based distribution company Reel Media International has distributed movies and series that have fallen into the public domain. That is, film and TV content that has lost copyright protections.

We began with less than 100 films, but now have 6,000 titles in our library. So what are the benefits and potential problems of having a public domain library to supplement what international distributors already have?

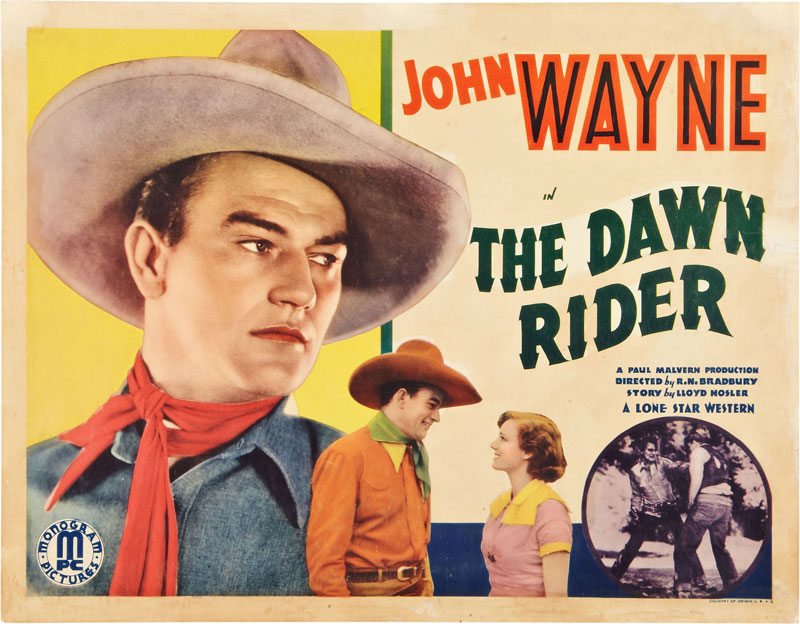

Public domain films can be real “evergreens” if they have recognizable stars. There are people who love to watch these films over and over again, and the movies are typically family friendly.

How do you know if a film is in the public domain? Just because someone has it on a list or someone says it is isn’t enough. In fact, that could result in a future lawsuit. We recognized this at an early stage and began paying for copyright searches to be done at the Library of Congress. Yes, these are expensive, and we have paid for over 15,000 copyright searches over the years, but we did what we had to do to be on the right side of the law.

There are many public domain films out there, but the quality of the master is sometimes less than perfect. Over the years, if we found a better film print or master, we would buy it in order to have the best possible quality. We’ve upgraded some titles as many as four times.

Just because a foreign film might be in the public domain in the United States, odds are high that it is not internationally. For many years, the copyright laws in the United States were different from those in Berne Convention Countries (like Belgium, Germany, France, Italy, etc.) until the U.S. finally signed the Berne Copyright Treaty in 1989.

Under U.S. copyright law prior to the mid-1900s, a film print had to be sent to the Library of Congress with the filing of a standard form. But there were production companies that simply never filed for a copyright, and so the film went into the public domain. Sometimes the production companies forgot to put a copyright notice at the beginning or end of a film, and with no copyright notice, when the film prints left the lab, it was automatically in the public domain.

If they did file for a copyright, they had to renew the copyright prior to January 1 of the 29th year after the release of the film. Many production companies either forgot or had ceased business by that time. Many felt that it was not worth it to renew the copyrights on low-budget Westerns, but our company has around 470 Western movies and 28 TV series that boast such stars as John Wayne, Randolph Scott, and Roy Rogers.

Starting in 1964, if a film had never been formally registered for a copyright, the copyright could be filed anytime in 95 years from the copyright notice that was placed on the film (without registration).

Here again time plays a part. Many production companies only produced one or two films and then folded. Or the producers are no longer alive to deal with all of this stuff.

U.S. copyright laws changed again in 1979. If someone filed prior to 1979 and wanted compensation from, let’s say a company that was selling or showing the film, they would have had to pay their own attorney’s fees. Practically, what we saw was simply a notice to cease selling the film, or they would agree on royalties from that point forward.

Starting in 1979, they could ask not only for the previous royalties, but also for attorney fees. Still, the income had to be a major amount to be worth filing.

We have found over the years that a number of younger entertainment attorneys had to be educated on the earlier copyright laws. Perhaps they thought they would only be dealing with new films.

With classic series one has to be extra careful, since not all of a series that someone claims to be in the public domain actually are. For example, the copyrights on the first 55 episodes of The Beverly Hillbillies (out of 274 total) were not renewed. Bonanza had 31 of 431 episodes without renewed copyrights, but there were episodes before and after those 31 that were renewed. Another example was Dragnet (1951). Using general numbers, the first 100 episodes were not renewed, the second 100 were, and the last 76 were a mixture of copyright renewals and non-renewals. There are cases where some video companies changed the title of what was thought to be a public domain series, not wishing to pay for a copyright search. We actually bought an episode guidebook to match against all the episodes we bought. It was very time consuming, but we discarded many episodes after we purchased them, as we discovered their copyrights were renewed.

But if a U.S. film is in the public domain in the United States, under Article 18 of the Berne Copyright Treaty, it is considered in the public domain elsewhere, and cannot regain its copyright. There are exceptions if a country has a law in place for whomever first registers the film.

We found over many years that some distribution companies would license films or TV series, claiming they had exclusive rights to the films, only for the licensee to discover later that the films were in the public domain. There have even been a couple of times we saw a company file for a number of copyrights, knowing that they would be rejected, but not before they had made a sale at several times what a public domain film should be priced. Copyrights can be filed for your version of the film if you have made changes such as colorization, or made changes in the film itself, such as music and editing or dubbing or subtitling in a foreign language.

As any distributor knows, demands for different sized images have risen over the years. We’ve had to increase our library to over 20,000 images (consisting of photos, posters, lobby cards, etc.) in the past few years. Those images for classic films have gotten harder to find and are a lot more expensive. Having dealt with video companies for many years, we were surprised to learn that a number of streaming companies did not want the stars to be listed on any of those images. Conversely, video companies would plaster the star’s name on the box cover to help sell the video version.

Bottom line, be careful when you license public domain films. Most importantly, pay for a proper copyright search, or deal with a company that supplies them as part of the price, and for technical questions, please consult your own entertainment attorney. (By Tom T. Moore*)

* Tom T. Moore is the CEO of Reel Media International, dba Reel Funds International, Inc. He first started exhibiting at the London Market around 1982, and exhibited at the first VIDCOM (now MIPCOM) in 1983. Based in Plano, Texas, Moore is also the author of six books.

Audio Version (a DV Works service)

Leave A Comment