James Brian McGrath (known as Brian to most) entered the television business in 1970, a year before the company he joined, a spinoff of CBS Syndication and CBS Cable, became Viacom. After that, McGrath’s career was always ahead of the curve. It was a rollercoaster of a curve at times, but he always seemed to come out on top despite tumultuous circumstances.

McGrath left Viacom just before the company went through internal management conflict. In 1981, he joined Columbia Pictures International, near the end of its own management turmoil, and a year before the studio was acquired by Coca-Cola. He left it in 1988, a year before it was sold to Sony.

In 1991, McGrath became president of the seven-year-old International Sports and Leisure (ISL) in Lucerne, Switzerland. He left in 1994, seven years before the company collapsed under debts amounting to $300 million in today’s U.S. dollars.

He joined Universal Studios in 1996, a year after it was acquired by Seagram from Matsushita, and left in 1999 before its disastrous sale to Vivendi.

In the process, he also managed to avoid the videotape format war between Sony’s Betamax and Matsushita’s (Panasonic) VHS.

The two competing Japanese companies assumed that Hollywood would ultimately select a de-facto format by using it for its home video content, so each decided to own its own studio. Even though VHS won consumer acceptance by early 1990, it enjoyed a relatively short period of dominance since it was replaced just seven years later by DVDs, which, in turn, was replaced by streaming in 2007.

A side note: After the 1989 NAB convention in Las Vegas, this writer met Sony’s co-founder Akio Morita at a press conference in New York City and casually mentioned that Panasonic was looking to buy Universal Studios (which would happen in 1990), at which point he replied that Sony was also going to own a Hollywood studio, in effect, anticipating the September 28, 1989 Columbia Pictures acquisition.

But let’s proceed in a less whirlwind fashion, because during several pauses in his television career, McGrath embarked on a few start-ups, the second of which was the Maryland-based Thoroughbred Racing Association (TRA), which he started working at while living in New York.

Here’s how one racing trade publication explained it: “Shortly after launching Equibase [a partnership between The Jockey Club and TRA to establish a central database of racing records], the TRA board pursued a national effort to market the sport, creating the position of commissioner and filling it in 1994 with Brian McGrath, a marketing executive. The effort was ill-fated from the start, and McGrath’s position was eliminated just 18 months later amid infighting among TRA member tracks.”

McGrath’s somewhat irregular path to television was through banking. After graduating at the age of 22 from Georgetown University in Washington D.C. in 1964 with a degree in International Business, he joined Chase Manhattan Bank in his native New York City. Two years later he was assigned to a branch that handled the CBS account.

In 1970, he was approached and hired by George Castell, the CBS treasurer. This is how McGrath recalled it: “He hired me as Director of Financial Services, reporting to him as Treasurer. My responsibilities included our banking relationships and Investor Relations.

“In the same year, [U.S. regulatory agency], the FCC, determined that networks [like CBS] should no longer be involved in film and television syndication, as well as the cable television business. CBS, being in both, decided that they would create a new entity, Viacom International Inc., and spin it off to their shareholders. I was technically a CBS employee [but] I went over to Viacom at the anticipated spin-off [which] was held up for about six months.”

McGrath further expanded: “The company they created, while relatively small, had some attributes that many other new entities of the time did not possess. It was a prime rate borrower from Morgan Guaranty and Chemical Bank, and had a listing on the New York Stock Exchange. To my mind it seemed that Viacom would be around for quite some time.”

Another perspective on how Viacom came about can be found in the 2007 book by Ralph Baruch, How I Escaped Hitler, Survived CBS and Fathered Viacom: “So, here was the deal: I was to lead a brand-new company whose board I did not know… with an oppressive contract dictated by CBS, with a number of executives cast off by CBS, an outside law firm in which I had no confidence, a costly employee benefits plan, an expensive lawsuit hanging over and a forfeited microwave license to connect many of our cable systems,” wrote Baruch.

Nevertheless, as McGrath later explained to VideoAge, “Fortunately, enough good decisions were made during the ensuing years that Viacom grew significantly, even to the extent that it ultimately acquired CBS [and Paramount], among other businesses.”

When the current major shareholder, Sumner Redstone, took over the company in 1987, he gave instructions to call it “VayaCom” — not “VeeahCom,” as it was previously known.

Continued McGrath: “[At Viacom] first as Assistant Treasurer and then Treasurer, I worked closely with Baruch, Terry Elks, Ken Gorman, Doug Dietrich and a number of other seasoned executives who went on to make their own mark.”

But new challenges soon arrived. He explained: “While I was Treasurer, Storer Broadcasting undertook an unfriendly takeover action [in 1977] to try to acquire [Viacom]. I was in California on business at the time and received a call from Baruch, who said, ‘You’ve got to come back to New York as soon as possible, we have a major problem.’ I was then charged with hiring lawyers, a proxy solicitation firm, and new investment bankers as our current one was in cahoots with Storer. We mounted a strong takeover defense. It was an exciting and nerve-racking time, but everything worked out in the end and Viacom retained its independence.”

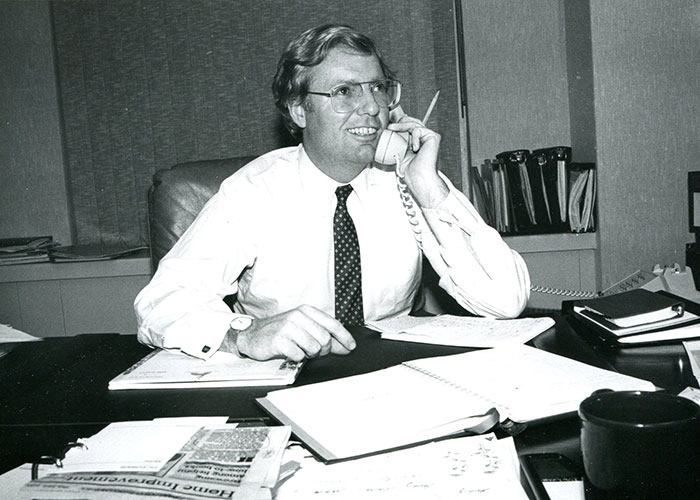

VideoAge reached McGrath first while at his summer home in Frankfort on Lake Michigan, then again after he returned to his Santa Barbara, California residence.

Even though McGrath lamented that VideoAge’s questions were interfering with his enjoyment of retirement, he joyfully provided answers.

“In the late ’70s, I set my sights on getting more closely involved in ‘the business of the business.’ I came from a family that was active in the steamship business around the world and I had studied International Business. I wanted to look for opportunities on the international side and got the chance [at Viacom] reporting to Larry Gershman, and got my first chance to attend MIP-TV in 1978.”

Added Gershman: “In 1978, my number two left Viacom and Brian moved over. He felt too limited in what he had been doing.”

The interesting aspect is that, as he explained in his 2015 book A Kid From Brooklyn, Gershman himself joined Viacom in 1976 from the TV station ad sales side of the business, and he too didn’t “know a lot about international [program] sales.”

McGrath continued: “In the early 1980s, Columbia Pictures was coming out of a state of turmoil. The challenges surrounding Indecent Exposure had subsided and Fay Vincent had been hired as CEO.”

Indecent Exposure: A True Story of Hollywood and Wall Street was a 1982 book written by David McClintick that traced the power struggles that began at Columbia Pictures in 1977 following the discovery of a check forged by the studio head at the time, David Begelman.

“The decision had been made to centralize all [of Columbia’s] international business activities in New York,” said McGrath. “Fred Gilson had succeeded Norman Horowitz as head of International Television and [the L.A.-based Gilson] had decided not to move to New York. Fred recommended me for the position and [in 1981] I was hired and reported to Pat Williamson, who was President of Columbia Pictures International.”

In 1982, Columbia Pictures was bought by The Coca-Cola Company for $750 million. Said McGrath: “I was asked in 1987 to move to Los Angeles as Executive Vice President of Coca-Cola Television reporting to Frank Biondi in New York. My responsibility was to put the pieces together, which included Columbia Pictures Television, Embassy Television, Merv Griffin and Columbia Telecommunications.”

Of that period, Nick Bingham, who was hired by McGrath from Thorn EMI Screen Entertainment in 1985, recalled when “Brian asked me to arrange a private audience with Pope John Paul II for himself and Fay Vincent, then-chairman of Columbia Pictures. I scratched my head before picking up the phone to Paolo Ferrari [our man in Italy] at the time, who was able to set it up and get me off a potential tricky moment.”

Bingham also mentioned that back then, “there was an unwritten understanding that the majors would kind of take turns doing big annual deals in the various territories in lesser markets,” before adding that McGrath’s “management style was laid-back, but knowledgeable and effective.”

Similarly, Michael Grindon, who was hired by McGrath in 1986 from the accounting division at HBO, remembered how he “was impressed with Brian’s management style. He would set the priorities and strategy and then let you get on with your work. He was not one to hover over his team, but he would be available if you had questions. He was fun to work with and extremely witty.”

In 1987, Bingham was appointed president of Columbia TriStar International Television and, in 1995 was promoted to president, International Sony Television Entertainment — a position taken over by Grindon when Bingham left in 1997.

Also in 1987, McGrath became president and CEO of Entertainment Business, International at The Coca-Cola Company, reporting to Vincent.

The events, however, did not unfold in such a schematic way. Indeed lots of whirlwind changes took place at Columbia Pictures between 1982 and 1988.

After the Coca-Cola acquisition, Columbia launched TriStar Pictures as a joint venture with HBO and CBS. In 1985, Columbia acquired Norman Lear and Jerry Perenchio’s Embassy Communications for $485 million, but it immediately sold the Embassy theatrical division to Dino de Laurentiis, who later folded Embassy Pictures into Dino de Laurentiis Productions, which eventually became De Laurentiis Entertainment Group, and which went bankrupt in 1989.

In 1986, Coca-Cola bought Merv Griffin Enterprises for $250 million. The following year, it spun off Columbia, which was sold to TriStar, with the latter becoming Columbia Pictures Entertainment.

In 1987, Coca-Cola also sold Embassy Home Entertainment to Nelson Entertainment.

From 1971 until the end of 1987, Columbia’s international distribution operations were a joint venture with Warner Bros. But Warner pulled out of the venture in 1988 to join up with Walt Disney Pictures.

Columbia was also involved in Spanish-language television with WNJU-TV in New Jersey. When it was sold in 1986, the new owner used it to form the Telemundo network.

While at Columbia, McGrath became involved with what we now call “windowing.” In a piece for VideoAge’s April 1985 Issue, he wrote: “The video revolution led virtually all major distributors to adopt a sequential-release pattern that offers product first to theaters, second to home video, third to pay-television and finally to television. The sequential-release pattern is a reflection of what appropriately might be called the ‘selective consumer-driven commercialization’ of television.”

Finally, the Columbia Pictures rollercoaster ride ended when the group was sold to Japanese electronics giant Sony for $3.4 billion in 1989. However, by then, McGrath had already taken a breather, having established his own consulting firm, which one year later took him back into the banking business as the head of Oppenheimer Entertainment and Leisure Time Investment activities.

Unbeknownst to him, in 1991, McGrath embarked upon yet another rollercoaster ride when he joined sports marketing company ISL Marketing AG in Lucerne as president and CEO. ISL (International Sports, Culture and Leisure Marketing was the complete moniker) was launched in 1983 by Germany’s Horst Dassler (son of Adi Dassler, founder of Adidas). Very quickly, ISL became involved with the International Olympic Committee (IOC), with whom it created The Olympic Program as the IOC agent.

In 1993, McGrath relocated to the U.S. as Chairman and CEO of ISL Holding (USA), which included managing the company’s marketing for the 1994 World Cup. “After three years in Europe, I wanted to go back to my family in the U.S.,” he explained, “and that expedient was a sort of transition.”

Just one year after McGrath left in 1994, ISL lost the rights to the Olympic Games, which was compounded by a loss of market shares, and began purchasing television rights on a large scale. This led to a cash flow crisis that ultimately felled the company, leaving a debt of U.S.$300 million.

Seven years after ISL collapsed in 2001, and following a four-year investigation by Swiss prosecutors, six former ISL executives — Daniel Beauvois, Christoph Malms, Hans-Jürg Schmid, Heinz Schurtenberger, Hans-Peter Weber and the former chairman Jean-Marie Weber — were accused of a series of charges, including fraud, embezzlement and the falsification of documents.

After the aforementioned TRA’s short-lived challenge, McGrath relocated from New York City to Los Angeles in 1995, going back to banking as an independent consultant to the entertainment and sports industries, which lasted just a year, since, in 1996, he joined Universal Studios as svp of International Business Development.

The following year he became president, International Recreation, with responsibility over Universal Studios Japan and theme parks in Spain and China. He also was the company’s liaison with Matsushita, since the Japanese group retained 20 percent of Universal Studios. Matsushita acquired MCA/Universal in 1990 for $6.6 billion and in 1995 sold an 80 percent stake to Canadian drink distributor Seagram for $5.7 billion. Subsequently, Matsushita sold its stake in Universal Studios in 2006 for $1.17 billion.

In 2000, France’s Vivendi entered a $34 billion all-share deal to absorb Seagram. In Hollywood, the new company was renamed Vivendi Universal and headed by Vivendi’s Jean-Marie Messier with Seagram’s boss Edgar Bronfman as vice chairman.

The deal with Vivendi turned out to be a disaster for Bronfman. Messier drove Vivendi to the brink of insolvency with a string of deals that left the company with $19 billion in debt. Bronfman (who had five seats on Vivendi’s 20-member board) led a boardroom crusade to oust Messier, and in July 2002 he won. In 2004, GE (which owned NBC) took over Vivendi Universal and renamed it NBCUniversal, which in 2009 was acquired by its current owner, Comcast.

In 1999, McGrath left Universal Studios to establish Halo Enterprises, once again focusing on entertainment and leisure-related investments.

He retired in 2000 at the young age of 58 after a 30-year career in the TV distribution industry.

(By Dom Serafini)

Audio Version (a DV Works service)

LOL