By Dom Serafini

Now that President Donald Trump’s administration has shut down the Voice of America (VoA) radio service, a welcome development for all the dictators who found that dissonant voice annoying, some of my small contributions to that service have come to mind.

In the early 1970s, shortly after arriving in New York, I spent weekends in the Bronx at the home of journalist Lino Manocchia to help him with his editorial commitments for radio, the sports weekly Autosprint, newspapers in Italy, and various Italian-American publications such as Il Crociato and L’Eco (of which he was also the editor), as well as the monthly he edited for the American women tailors’ union, Giustizia (his main source of income).

I had met Manocchia through my aunt Iole as she was a cousin of his wife Ada. Manocchia had taken a liking to me as a young contributor to several magazines in Italy. At that time his only son Adriano (my contemporary) wanted to establish himself as a singer-songwriter.

I’d leave on Saturday mornings from where I was staying at my aunt Iole’s house in Copiague, on Long Island, with my second- (or maybe third-) hand Chevrolet Impala convertible, driving along highway 495, which merged with the 295 to cross the Throgs Neck Bridge and arrive in the Bronx via the 95, which took me to the Monticello area, where Manocchia lived.

Autosprint was edited by his friend Marcello Sabbatini from Teramo. Like me, Manocchia was from Giulianova, a town in the province of Teramo. The newspaper Giustizia consisted of a few signatures and had various editions. Manocchia edited the monthly Italian version, so he had plenty of time for extra activities and needed to go to the editorial offices in Manhattan only a few days a week via the subway.

Among Manocchia’s various commitments was the radio service Voice of America. My tasks were to translate articles into Italian that he selected (from the pile of newspapers that he accumulated day after day), prepare the teletype paper tape, and occasionally lend my voice for an interview for Voice of America’s Italian service. VoA was born in 1942 and broadcast in 45 languages, including Italian, with reports sent from New York and Washington, D.C.

In those years America was seen in Italy as the bad “Amerika” and the Communist Party of Enrico Berlinguer was the second-largest in Italy. That was when talk about the “Historic Compromise” started to emerge. That was about allowing the Communists to be in government, and was favored by the leader of Italy’s main party, Aldo Moro, but it was frowned upon by U.S. Secretary of State Henry Kissinger. (in that period, I had the opportunity to talk about this all during a brief meeting with Kissinger, but he didn’t go into the details). At that time VoA was indeed the voice of America, but it did not delve into politics. Manocchia’s VoA services were human interest pieces: a cultural service that, however, still worked at an ideological level to strengthen the America dream.

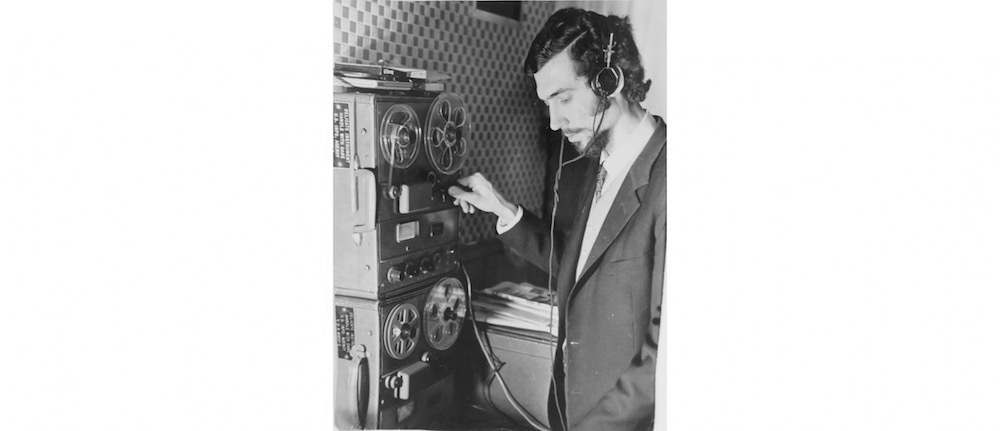

These radio services were recorded at Manocchia’s house, a two-family dwelling with three floors. When it was time to record he retreated to the basement where he had added a kitchenette and a bathroom. In one corner he kept the Teletype model 33 that he used to send articles, and the vertical tape recorders (assigned by VoA, as can be seen from the plate on the recorders in the photo with this journalist). On the desk was the kit for editing the audio tapes, consisting of a splicing block, a single-edge razor blade, adhesive magnetic strips, and a felt pen with which he marked the parts of the tape to be eliminated. The reel that he carefully edited was then sent to VoA headquarters (I believe in Washington, D.C. at the Wilbur J. Cohen Federal Building).

At that time, and until recently, VoA was followed by 400 million listeners worldwide, especially by those in authoritarian countries such as Russia, China, and Iran. The closure ordered on March 14, 2025 occurred because for too long VoA was deemed too “liberal” and, recently, “anti-Trump.” Yet Manocchia was not a progressive. On the contrary, he was rather conservative, possibly as a reaction to his birthplace which had been “red” for years. This is despite the fact that he had suffered for two years in Nazi Germany as a prisoner of war (beginning in 1943). He did not like to talk about his POW years, but before dying at the age of 96 in 2017, he collected his recollections into the book Frammenti di un prigioniero (Fragmented Memories of a Prisoner), which was published posthumously in 2022.

Leave A Comment