By Dom Serafini

Justice Samuel Alito summarized the Social Media position before the U.S. Supreme Court (here paraphrased): “You say it’s like the Miami Herald (or any other newspaper), and the States say it’s like a telegraph company that just delivers messages.”

The court is set to decide whether some U.S. state laws can prevent online platforms (like Facebook, YouTube, and X, formerly Twitter) from moderating users’ posts.

The case began in 2021, when then President Donald Trump was banned from Twitter after inciting the Capitol riot. After January 6, conservative states like Texas and Florida passed laws requiring that platforms post nearly all content posted by users (without censoring them), regardless of what viewpoint the users expressed in their posts.

The trade group representing Social Media (Meta, Google, and X) first sued the states in lower courts, but the suit ultimately reached the Supreme Court, and lawyers for the trade group maintained that the states’ requirement infringed on their First Amendment rights.

The states’ position is that platforms don’t have to block users’ content because users are free to block unwanted content themselves. Plus, the platforms are defined as “modern public squares,” and the state of North Carolina has already found that it is unconstitutional to banish sex offenders from these modern public squares.

Chief Justice John Roberts explained that the First Amendment bars the government from telling Social Media platforms what they must or can’t say, but it doesn’t impose requirements on private parties.

All this posturing brings to mind two simple considerations. First, Social Media publishes content from users and from themselves, therefore they’re publishers, and as such they’re responsible for what they publish, and therefore they need to control the content. Second, the states confuse publishers with a delivery service, like a telegraph company.

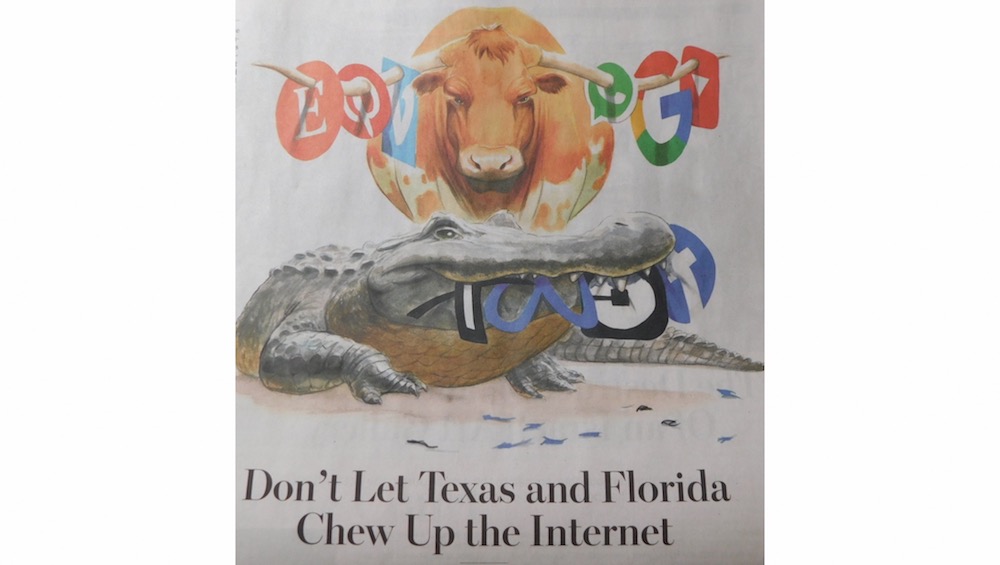

Two prominent advocates argued in The Wall Street Journal not to “Let Texas and Florida Chew Up the Internet,” and muddied up the waters. They are: Daphne Keller, director of Platform Regulation at Stanford Law School, and Francis Fukuyama, a senior fellow in Stanford’s International Studies’ division.

According to the duo, “Courts regularly strike down laws under the First Amendment not because better regulation is available. Technical tools do exist to put decisions about lawful speech in the hands of individual Internet users. Texas and Florida shouldn’t be permitted simply to disregard that option and impose their own rules.”

But, in effect, what the two advocates are proposing is exactly what the states are requesting — that we treat the platforms as mere messengers, and not the publishers that they really are.

Leave A Comment