By Dom Serafini

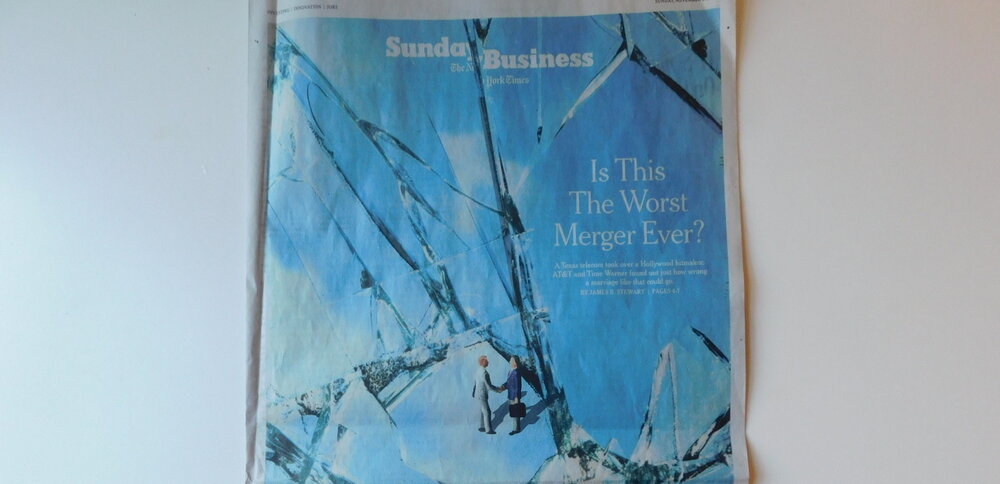

There was a fascinating story published in the Business section of the November 20, 2022 edition of The New York Times. It took five full pages (out of the section’s 10) to describe, in detail, why the AT&T takeover of Time Warner was a financial, strategic, and structural fiasco.

The feature had two headlines. The cover said: “Is This the Worst Merger Ever?” And a second one at the beginning of the story said: “How a Media Megadeal Went So Bad So Fast.” One of the conclusions reached in the piece was that between Warner Media and DirectTV (another megadeal gone sour), AT&T “squandered close to $100 billion.”

A bad precedent was set in 2000 with the Time Warner merger with AOL. That deal resulted in a $160 billion loss, clearly indicating that technology companies shouldn’t merge with content companies. Unfortunately, it’s pretty obvious that no one paid attention to this, though.

In these cases, the key problem (at least in this journalist’s view) is that when top corporate executives talk about synergy, they don’t have the coordinates clear in their minds and seem to confuse “vertical integration” with “horizontal integration.” The first is between companies in the same sector and the second is between companies in different industries. And, if one would like to add a historical prospective, they can travel back in time to 1999’s ill-fated acquisition of Argentina’s Telefe by Spanish telephone company Telefonica.

The NYT feature, written by James B. Stewart, a Pulitzer Prize winning lawyer, and a columnist for the Times, used the first half of his lengthy article to explain the cultural differences between the Hollywood studios and the telephone group.

This can be gleaned from a story in the piece about a directive given by John Stankey, who served as AT&T’s COO and CEO of Warner Media in 2018, to studio executives. He told them that the default length for meetings should be 30 minutes and that Saturdays were reserved for quality time with his family.

Right off the bat, this request clashed with the Hollywood mantra, “If you don’t work on Saturday, don’t bother coming in on Sunday.”

But the more substantive parts came in the second half of the article, where several issues were explored. First was the fact that AT&T was betting on a streaming platform model. “Stankey elaborated that there were likely to be only a few large streaming survivors and that he wanted HBO Max to be one of them,” Stewart wrote.

The second issue was AT&T’s request that Warner stop being “the Switzerland” of content (meaning that it supplied competitors with content), and reserve Warner’s output for HBO Max.

This request would put $7 billion in revenue at risk, and a heated streaming competition would increase expenses to $9 billion a year. The Times story reported that, according to (now) Warner Bros. Discovery CEO David Zaslav, HBO had gone from $2 billion in profits in 2019 to a loss of $3 billion in 2022.

But the Times feature had a more important message for the industry that can be read in between the lines — that Wall Street-inspired mergers are seldom winning propositions. The first clue came early on in the Times story when the author wrote: “Since AT&T’s stock price had gone nowhere [AT&T] saw media as a much-needed path to growth.” The second clue came towards the end of the story: “AT&T intended to spin off Warner Media and, given Wall Street’s infatuation with streaming, a stand-alone news service alongside HBO Max would add value.”

Then came the conclusion: “It was their misfortune to make a multibillion-dollar bet on streaming just as investors’ infatuation with the model started to fade.”

Leave A Comment