What happened to Michael Cimino? The acclaimed Italian-American filmmaker rose to fame with his 1978 war drama The Deer Hunter, which won five Academy Awards, but his follow-up film, 1980’s Heaven’s Gate, an epic American Western, was a box-office bomb. The critics and audience response were so poor that United Artists ended up pulling it from theaters, with the popular myth being that UA tanked two years later due to this cinematic failure. Cimino’s pull on Hollywood was never the same afterward.

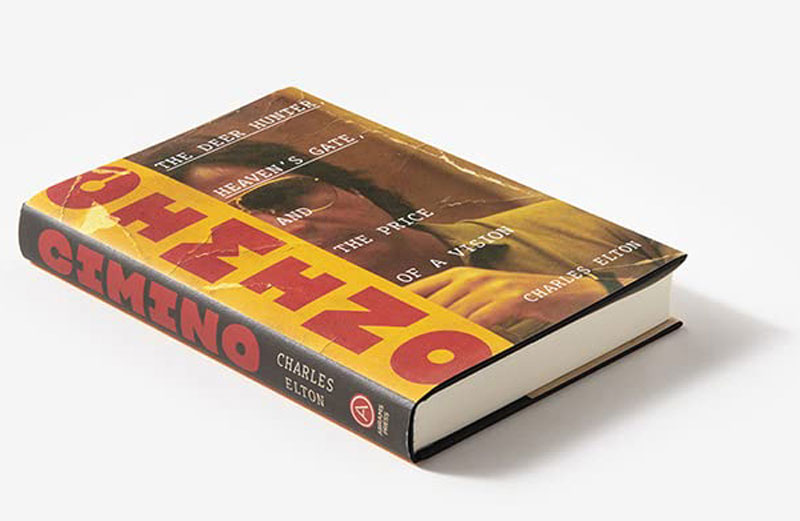

Author Charles Elton tackles the life and career of Cimino in his latest book, Cimino: The Deer Hunter, Heaven’s Gate, and The Price of a Vision (352 pgs., Abrams Press, 2022, $28). The biography looks at the span of Cimino’s life and demystifies the hearsay around his fall from grace in Hollywood, with chapters dedicated to his childhood, his early career in directing commercials, his films, and what happened after the release of Heaven’s Gate. Cimino is the perfect subject for a biography, and in Elton’s hands, he is shown to be as complicated a man as he was. “Of all Hollywood directors,” writes Elton, “Cimino is one of the most fascinating, mysterious, and enigmatic figures, both reviled and praised, his controversial behavior well-documented but often misunderstood.”

Cimino was born in New York City on February 3, 1939. As Elton notes, Cimino often self-mythologized by offering contradictory information in interviews. “Sometimes Cimino said he was born in 1952, sometimes in 1943.” Elton doesn’t dwell too long on Cimino’s childhood, but notes that he was raised outside of the city in Westbury. His parents were Italian immigrants, but Cimino seemed detached from his cultural heritage. “He never talked about his Italian roots and tended to avoid questions about the date his family emigrated to the U.S. or even where they came from,” writes Elton.

He studied graphic art at Michigan Stage, pursued grad school at Yale, then moved to New York City, where he got into directing commercials. “Cimino’s commercials break the rules,” comments Elton. Of an early Pepsi commercial, Elton notes: “It looks like it was shot by Jean-Luc Godard on a day off from À bout de souffle with a kinetic energy and a kaleidoscopic array of effects — jump cuts, point-of-view shots, slow motion, rack zooms, vertigo-inducing camerawork.” In his commercial directing career, Cimino came across Joann Carelli, an agent who would become an influential force in his life. Carelli would be many things to Cimino, including lover and loyal confidante, but she also served as a producer on Cimino’s major films.

Cimino got his start as a screenwriter in Hollywood, where he was represented by the persuasive Stan Kamen at William Morris Agency. Among projects he wanted to work on, one was an adaptation of Ayn Rand’s The Fountainhead. He soon found himself with an opportunity to come up with the script for Thunderbolt and Lightfoot which he wrote with Clint Eastwood in mind. Cimino went on to write the script, as well as direct the feature.

With 1978’s The Deer Hunter, Cimino achieved the glory that most filmmakers want. Featuring stars such as Robert de Niro and Christopher Walken, the war drama revolves around three steelworkers who were greatly affected after fighting in the Vietnam War. It was nominated for nine Academy Awards in 1979, and it won five, including Best Picture and Best Director. “The Deer Hunter has never lost its power,” says Elton. “It is still remembered as the most influential and visceral of all the Vietnam movies.” The high of critical acclaim and box-office success allowed Cimino to make his next film, Heaven’s Gate.

Heaven’s Gate was inspired by the Johnson County War, a frontier conflict that took place in Wyoming from 1889 to 1893. The film starred an unbelievable cast that included Kris Kristofferson, Walken, Jeff Bridges, and Isabelle Huppert, among others.

One of the problems with the film was the budget, which was initially set for a cool $11.5 million but ballooned to $40 million ($144 million in 2022 money). With poor theater attendance and harsh criticism, it was no wonder UA withdrew the film. Elton outlines the difficulties and interpersonal conflicts that beset the making of the film, and he helpfully offers historical context as to why United Artists decided to work on the film. One important point comes down to where UA was at in its own trajectory. Following its acquisition by Transamerica in 1967, the studio had new leadership through the next decade. “With such an undynamic and unproven team at the helm,” writes Elton, “the studio was not at the top of anyone’s list for submitting projects to,” which was one of the reasons the studio took on the risk of Cimino’s film.

With Cimino, Elton has drawn a compelling portrait of the filmmaker, who died in 2016. The tragedy of Cimino’s story is not of a failed artist but one thwarted by an industry. Years later, Cimino’s work, including Heaven’s Gate, has been reassessed, with critical adoration. As early as the start of the book, there’s the sense that, although Cimino’s cinematic output dropped later in his life, he still had much more to offer cinema. “In the last 20 years of his life, he did not direct a single movie,” writes Elton. “Instead, inside the house, he worked constantly. He said he had written at least 50 scripts, although few people know exactly what they were.”

(By Luis Polanco)

Audio Version (a DV Works service)

Leave A Comment