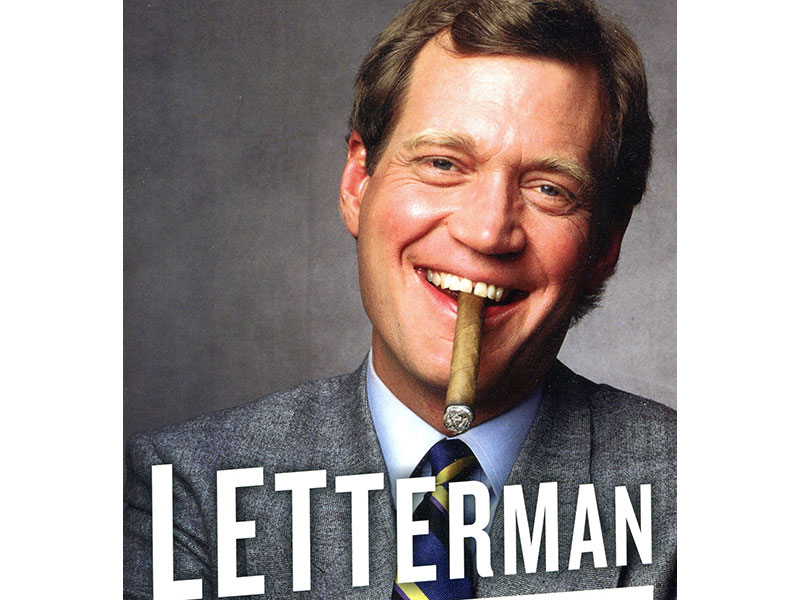

Among the recent class of late-night TV talk show lightweights in the U.S., which include such names as Jimmy Fallon and Seth Meyers, David Letterman stands as the closing act of a bygone generation of TV jokesters. Or so Jason Zinoman reasons in his recent biography of the former CBS television host and comedian, Letterman: The Last Giant of Late Night (Harper, 2017, 368 pages, U.S.$28.99), a book that explores Letterman’s life, with specific focus on his career at NBC.

Zinoman suggests that Letterman is an enigma within the entertainment industry, describing him as “a talk-show host who didn’t always seem to enjoy talking to people, a reserved man who spoke to millions of people every night, one of the most trusted entertainers of his time, whose ironic style kept emphasizing his own insincerity.”

Despite his ironic detachment and comedic posturing, Letterman, according to Zinoman, is “a tortured personality with a self-lacerating streak,” who, at the same time, is approachable for the unassuming white guys of Middle America. For example, Zinoman writes, the beloved curmudgeon “represented a version of New York cool that seemed more accessible than punk singers in ripped shirts or dapper sophisticates on Broadway. He wore white sneakers, unkempt hair, and a conspiratorial expression.”

At certain moments in Letterman, Zinoman expounds on his subject from the rose-tinted perspective of a faithful worshiper. “I became a devoted David Letterman fan not long after I first turned on a television,” he boasts. But Zinoman’s book is at its most provocative when he isn’t able to reconcile Letterman’s real contradictions between his on-air personality and his off-stage relationships. A notable element of the biography is Zinoman’s spotlight on Letterman’s collaborators, especially on Merrill Markoe as a prominent behind-the-scenes character.

Markoe, Letterman’s longtime girlfriend and working partner, appears as a pivotal figure in Letterman’s career. She was crucial to the development of Letterman’s stand-up and comedic voice on television, inaugurating a creatively adventurous period for both the couple and TV. “Just as she wrote jokes for his stand-up act, Markoe developed ideas for the show that would eventually become standards,” Zinoman writes. In the first week of broadcast for The David Letterman Show, a short-lived NBC morning talk show, Markoe introduced Stupid Pet Tricks, as well as later routines, such as Small Town News. She also began to produce and edit film clips, known as “remotes,” on the streets of New York City. “Markoe’s greatest contributions were the filmed remote pieces,” which Zinoman describes as portraying “Letterman as the sensible, sarcastic man in a city full of eccentrics and fools.”

Due to poor ratings, The David Letterman Show was canceled, causing a hiccup in the relationship. “The ending of his show had also wreaked havoc on his relationship with Markoe,” writes Zinoman, who recounts harsh words Letterman once said to Markoe: “‘If it wasn’t for you and your crazy ideas,’ he said angrily, ‘I’d still have a talk show like John Davidson.’”

A short while later, Letterman was contacted by NBC for a new show, to be called Late Night with David Letterman, which would follow the program of his childhood hero, Johnny Carson. “In the early 1980s, Letterman was a fairly traditional host putting on an often experimental show that was literate, daring, and often baffling. His persistent target was television itself and, more specifically, the talk show, scrambling its conventions, shifting perspectives, and blurring the line between real and fake,” notes Zinoman. “By the middle of the decade, Letterman’s performance had become more confidently theatrical, and Late Night had evolved, marked by extravagant stunts, an absurdist streak, and show-length parodies.”

Letterman’s public distaste for aspects of television and celebrity culture made its way onto the program through his jovial, sometimes mean-spirited, banter toward guests and onscreen associates. Among the program’s coterie of personalities, Paul Shaffer, the music director, “became a punching bag standing in for a certain kind of entertainment figure.”

In the past, VideoAge has decried Letterman’s antagonism towards journalists, however, this tidbit is not included in Zinoman’s book, nor is the after-publication fact that Letterman is returning in a “binge”-way on Netflix.

At the beginning of Late Night, Zinoman relates that Letterman’s self-deprecating temperament would be acted out on Markoe’s work. In a 1982 entry of Markoe’s diary, of which Zinoman incorporates bits, she writes, “The last 10 months have included a nightly discussion about what a failure we are. Sometimes it is just Dave blowing off steam, working out his insecurities but often I am the wrong recipient of this info because it includes an attack on the work I have been doing all day.” As a resolution, Markoe stepped down as head writer, but would continue to regularly contribute remotes and work as a consultant.

As Zinoman notes, in her mid ’80s stint as head writer, Markoe had a significant role in hiring the program’s young writing staff, which “was composed entirely of white men” who were attracted by the “prankish fraternity house strain to Letterman’s humor.” Two such writers were Tom Gammill and Max Pross, Harvard graduates, who brought on their friends, as well as Ivy League wit and pretension. At the time, Zinoman remarks, “there was almost no serious discussion of racial or gender makeup on the staff.”

In the late 1980s, NBC experienced a writer’s strike that deeply affected Letterman’s show. In response to the protests, Zinoman points out, “Letterman proved that he could put on a funny show without writers,” but as a result, “his relationship with the writer who had helped create Late Night with David Letterman ended.”

In the midst of everything, Letterman began expressing gloom about his health, to which Markoe answered, “Look, you are either dying or dating. You can’t be both.” In fact, Markoe soon discovered that “she wasn’t the only woman in his life.” Letterman had been cheating on her with Regina Lasko, the unit manager of Late Night, now his current wife.

In the later years of the Late Show with David Letterman on CBS, his sexual infidelities would catch up to him, culminating in the October 1, 2009 episode, which included an on-air confession of workplace affairs to an off-set blackmail action against him. Just seven months prior, Letterman and Lasko had officially married.

Upon elaboration of Letterman’s two-timing pursuits, Zinoman’s fan-boy enthusiasm is quelled and reaches a tone of somber realization: “David Letterman had just confessed to cheating on his wife multiple times, with women who worked for him, an imbalance of power that was, at the very least troubling. And his audience actually applauded.” The scandal, Zinoman explains, “called into question what people know about him, and exposed a certain boys’ club sexism that had been lurking under the surface.”

Never definitively stated, Zinoman implies that Letterman’s indiscretions contributed to his “hilarious portrayal of this difficult, fascinating and self-lacerating character, who hated revealing himself in his work but couldn’t help doing so.” Put another way: “Letterman gave all of himself to television,” Zinoman writes, “but he needed help.” Letterman is equally compelling when its author avoids the celebrity mythologizing of “the host and his eccentric personality” that was integral to the latter part of his late-night career, and addresses Letterman’s earlier affinities with collaborators. In all, Letterman is a comprehensive testament to the nature of genius as it leans on the work of others.

(By Luis Polanco)

Audio Version (a DV Works service)

Leave A Comment